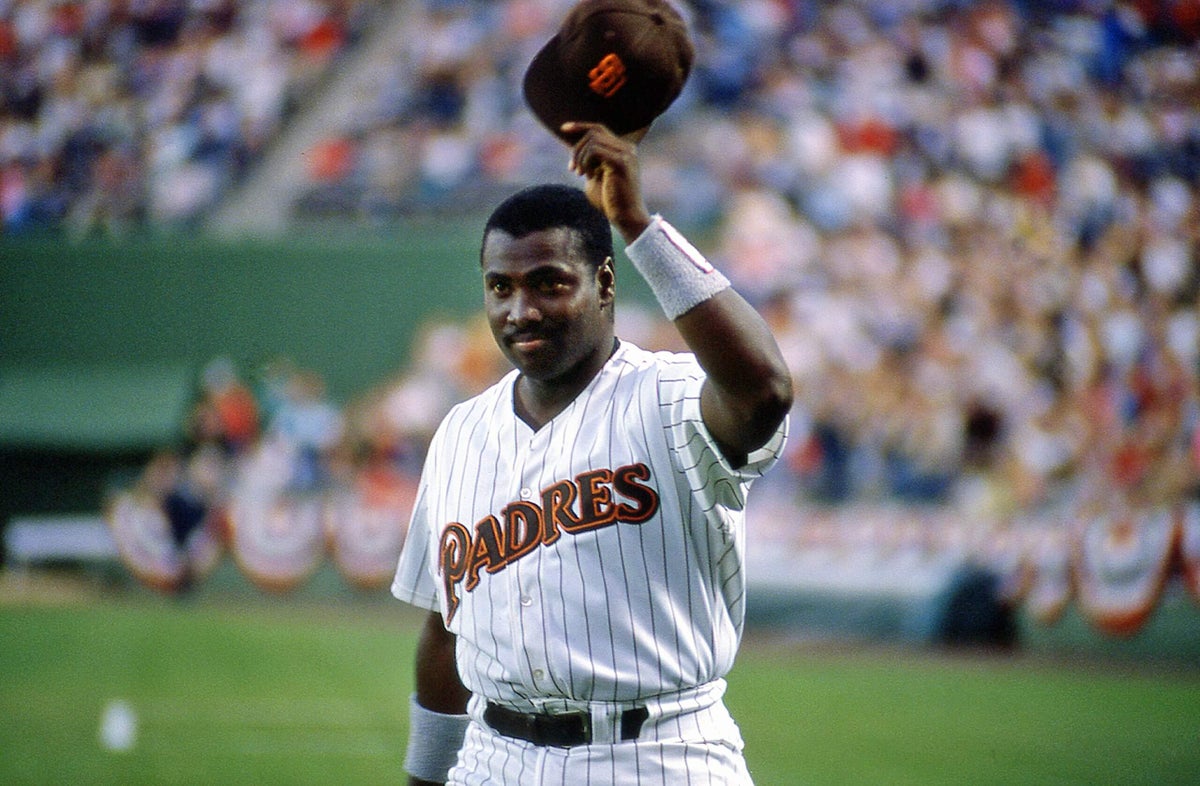

Welcome to Sliders, a weekly in-season MLB column that focuses on both the timely and timeless elements of baseball.

The aspiring ballplayer could find it hard to concentrate in class. As a student at San Diego State, Seby Zavala would let his mind wander to his favorite lunchtime hangout, the one that served no food, just wisdom from a professor without peer: Tony Gwynn.

“He would sit in the dugout and eat his lunch every day, so I would get out of class and go straight to the dugout, just to talk to him,” said Zavala, a catcher in the majors for parts of the past four seasons. “To be able to sit there and talk to a Hall of Famer about baseball or life — he didn’t care if you asked questions, he just wanted you to have a reason behind it. I would think of questions all day: How can I get better, what don’t I understand?”

Gwynn, the greatest pure hitter born in the last hundred years, would have turned 65 on Friday. He was the San Diego State baseball coach when he died of salivary gland cancer in 2014, and Zavala is one of three players from his final season who reached the major leagues, with Ty France of the Minnesota Twins and Greg Allen, an outfielder now in the minors with the Chicago Cubs.

“Those guys got to know him on a much closer basis than most,” Tony Gwynn Jr., now a Padres radio analyst, said at Yankee Stadium this week. “Even though he was sick when they were around him, they still got a piece of him that most people don’t get a chance to really experience.”

Zavala, who is now in the Boston Red Sox’s system, missed one of his college seasons with an injury. Gwynn, who had pioneered video study as a player, made Zavala the team videographer. By the end of the season, Zavala said, he was thinking along with the pitchers, predicting outcomes, unlocking a new vision that would carry him to the majors.

“That’s how I learned to read hitters, how to set them up and make them do what I want them to do,” said Zavala, who has played for the White Sox, Diamondbacks and Mariners. “I look at the game differently because of all the things he taught me. I don’t think I’d be here without him.”

Zavala, France and a student manager, Cooper Sholder, got tattoos together commemorating Gwynn after he died. In the 11 years since, France said, he has come to appreciate Gwynn’s humility and accessibility.

“He did such a great job of humanizing himself, making it seem like he was not ‘Mr. Padre’ or San Diego’s greatest baseball player,” France said. “He was just Coach Gwynn, and to this day, I still refer to him as Coach Gwynn.”

Gwynn won eight batting titles in 20 seasons while collecting 3,141 hits. He could have gone 0-for-1,000 after he retired and still hit .305 — higher than the hit king, Pete Rose. Gwynn’s .338 career average is the best of anyone who spent his entire career in the integrated major leagues. Wade Boggs and Rod Carew are tied for second, 10 points behind the master.

“He just had a magic bat,” said Ron Darling, the former Mets righty who held Gwynn to a mere .441. “I gave up two hits to him that bounced, like cricket. Two bullets on balls that bounced.”

Gwynn hit .397 (50-for-126) off Greg Maddux and Pedro Martínez, with no strikeouts. John Smoltz fanned him once while giving up a .462 average (30-for-65). Gwynn owned almost everybody: forkballers (Hideo Nomo, .560), knuckleballers (Tom Candiotti, .422), Cy Young Award winners (Doug Drabek, .469), World Series MVPs (Curt Schilling, .390), Leiter brothers (Al and Mark, .452) — on and on and on.

The numbers tell a story, and they can always be savored. But as time goes on, fewer active players will have known the man behind them.

“The stats are the stats, but the person — he was always so gracious with his time,” said Padres TV analyst Mark Grant, a former teammate. “In the old days, guys had their little mail cubbies in the clubhouse. Mine would have a gift certificate from Pizza Hut or something; his would just be stuffed. And he would actually bring shoeboxes of fan mail on the road to catch up on it in his hotel room. He was the whole package.”

Late in his life, Gwynn Jr. said, his father could see where the sport was going. Velocity was rising and hitters were increasingly incentivized to choose power over artistry. Today’s bat-to-ball specialists, like Luis Arraez and Jacob Wilson, would have warmed his heart.

Yet while Gwynn famously served singles the opposite way — “There’s hits all over the field,” France said, repeating a mantra — he was far more than a slap hitter. In the last nine years of his career (1993 to 2001), Gwynn had his typical .356 average and .400 on-base percentage, but also a .500 slugging percentage. He averaged 13 homers a season, almost double his previous rate.

In his first game at the old Yankee Stadium, in the 1998 World Series, Gwynn homered off the facing of the third deck. Another hitting wizard from San Diego, Ted Williams, would have been proud.

“That was something I don’t know that he would have been capable of doing — or would have been willing to try to do — in the first 10 years of his career,” Gwynn Jr. said. “He learned that after his conversation with Ted in ’92 or ’93, telling him that, ultimately, you can have both.

“In order to get them to go out here (outside), which you want, you’ve got to get them out of here (inside). How are you gonna do that? If you’re just inside-outing singles to left, they’ll just keep (pitching you in), so you’ve got to start turning on some of these balls. He realized he didn’t have to give up his average or the things that he enjoyed in order to do that.”

Williams made a similar point in a 1995 interview with Gwynn and Bob Costas: “That’s where baseball history is made — from the middle in!” Williams was in his late 70s then — he lived to be 83 — and Gwynn said he wished others could have the same opportunity to absorb such wisdom.

“You can learn so much just from talking to people,” said Gwynn, who lived by that credo and passed it on.

France, a former All-Star who is now the Twins’ regular first baseman, said Gwynn would be “livid” at the state of modern hitting, especially all the strikeouts. France already has 100 or so more career strikeouts than Gwynn, in roughly 7,000 fewer plate appearances. It wasn’t always easy playing for a legend.

“I mean, he was just the greatest of all time,” France said. “Being able to do it for as long as he did, he didn’t understand that not all of us are him, and he would get upset and frustrated with us for not being as good as he is. He just held us to such a high standard.

“And while you’re going through it, you don’t really understand. You’re trying to figure out, ‘Why is he picking on me so much? Why does he want me to be him, essentially?’ But he just wanted the best for you. That was his biggest thing.”

The best of Gwynn, on the field and off, was about as special as anything we’ve ever seen. Happy birthday, Mr. Padre. And thank you.

Gimme Five

The Yankees’ Tim Hill on submarine pitching

Tim Hill entered the weekend needing two appearances for 400 in his career — a round number, but still more than 400 away from the leader in games pitched by a submarining lefty. Former Yankee Mike Myers made 883 appearances in his 13-year career, the most ever by a low-angled southpaw.

“I’ve watched a lot of his stuff,” Hill said. “He’s a legend.”

Legend — or the stuff of legend, anyway — could also describe Hill, now in the eighth season of a most unlikely career. Hill, 35, has Lynch Syndrome, a hereditary condition that increases the risk of cancer. As a Royals minor leaguer, he missed the 2015 season while fighting Stage 3 colon cancer, the same disease that had taken his father, Jerry, when Hill was in high school.

Hill did not enroll in college, but sometimes helped his sister in her job at a warehouse in San Diego.

“We would be playing tape ball in the warehouse and a couple of the guys that played, they told me they had an adult league team,” Hill said. “We were up in Carlsbad, a little north, and I was like, ‘I want to go play with these dudes.’ In the beginning, they were funny, they’re like, ‘Are you sure? It’s pretty competitive.’ I was like, ‘I think I could hang.’”

An opponent was impressed and encouraged Hill to try out for a nearby community college. He made it, then transferred to a four-year college in Oklahoma and finally reached pro ball at age 24. Four years later, he was pitching for the Royals.

Released last summer by the worst team in baseball, the Chicago White Sox, Hill wound up in the World Series with the Yankees, fearlessly flinging sinker after sinker. He has a 2.34 ERA in 51 games for New York, and recently shared five insights into his distinctive style.

Act naturally: “I’ve always thrown like that, even as a kid. When I get into a powerful position, my torso bends. So, really, my arm angle is not that low, it’s that my torso’s bent. I can throw a ball overhand, but if I try to throw it hard, I throw it the way I throw it. If you watch me in catch play, that’s exactly how I throw a baseball. And then on the mound I might get a little lower, just trying to get down there a little earlier. So I would say, in catch play, I’m maybe close to like four feet (off the ground). And then when I pitch, I’m down to like three.”

Defy the conventional: “At one point (coaches) were like, ‘Let’s try to make him throw overhand, we think he could throw really hard if he threw overhand.’ I was throwing it pretty good from where I was throwing it, but anyways, we did it and it just wasn’t good. And my dad was like, ‘All right, leave him alone, let him do what he does.’ So that was that.”

Seize the O’Day: “A lot of the guys that throw like me, they spin the ball a lot more than I do, so it’s a little different. Darren O’Day was the first one I saw that was throwing from down here and throwing four-seam fastballs up. I was in Double A at the time and I was like, ‘I think that looks pretty good.’ Which is funny, because I don’t really do it as much anymore, but it’s still in there.”

How do you spin a breaking ball from that angle? It’s a mystery: “I haven’t really figured that one out, because I don’t throw many breaking balls. I throw sinkers and four-seams. I throw sliders too, but it’s definitely not my strength.”

His infant son just might be a lefty, too: “I have his right hand tied behind his back right now, so we’ll see.”

Off the Grid

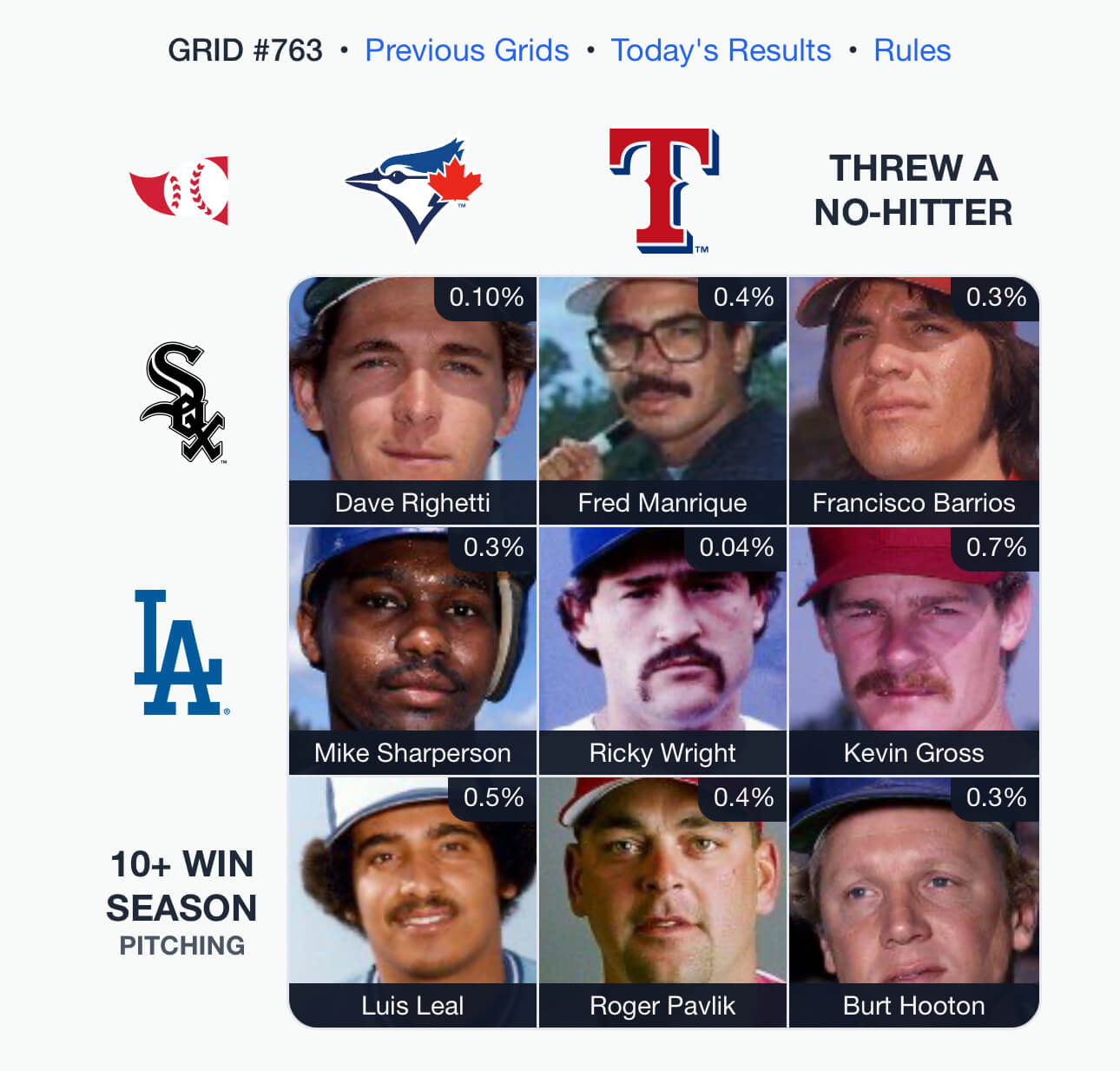

Kevin Gross/Dodgers no-hitter

Which pitcher did you see most often as a kid? Not your favorite pitcher; that’s different. Who logged the most innings while you watched? For me, it was Kevin Gross. In my formative years as a baseball fan (ages 7 through 18), Gross made the most starts and threw the most innings for my hometown team, the Philadelphia Phillies.

He wore K. GROSS on his back because the Phillies — inexplicably, to a kid — had two players with that funny last name (also Greg, a pinch-hitting specialist). A tall righty with curly hair and a mustache, he was a visual cacophony for hitters, elbows angled like a suspension bridge in mid-delivery. He had a tic of rolling his left shoulder after every pitch, flipped a lot of curveballs, and painted wildlife scenes in his spare time.

“I wish I was a little better artist when I was a pitcher,” Gross told the Dodgers’ team historian, Mark Langill, in 2022. “It’s like artwork, you have to hit corners and be consistent.”

At various points in his 15-year career, Gross led his league in five categories, all negative: losses, earned runs, home runs, walks and hit batters. He once served a suspension for having sandpaper in his glove, and he never appeared in the postseason.

Even so, Gross had his moments. He pitched in the All-Star Game for the Phillies in 1988 and threw a no-hitter for the Dodgers four years later. On the final day of the 1993 season, his complete-game six-hitter knocked the 103-win Giants out of the playoffs. Later, Gross helped the Rangers win their first division title.

He’s a useful guy on the Immaculate Grid and fit into four squares last Sunday: Rangers/Dodgers, Rangers/10-win season, Dodgers/no-hitter and no-hitter/10-win season. Basically, Gross took the ball over and over for 15 years and never got hurt. Given the fragile state of modern pitchers, there’s a lot to be said for that.

Classic Clip

Derek Jeter’s commencement address at the University of Michigan

There’s a famous story about the Yankees’ draft room in 1992. As the team considered choices for the sixth overall pick, someone mentioned that Derek Jeter, a high school phenom from Kalamazoo, Mich., might take a scholarship to the University of Michigan.

“He’s not going to Michigan,” replied scout Dick Groch. “He’s going to Cooperstown.”

Groch was right, of course, though Jeter did take some offseason classes at Michigan as a minor leaguer and has long been an avid fan of the Wolverines. Last Saturday, the school welcomed him as commencement speaker to the class of 2025.

“As of today, all of you have made it further in school than me — as a matter of fact, I think technically I’m still a freshman,” said Jeter, who was given an honorary Doctor of Laws degree. “It is actually a relief, because I started worrying that my kids would get a degree before me — and they are seven, six, three and two. But, let’s be fair, I took a slight detour to fulfill my lifelong dream of playing baseball for the New York Yankees.”

Jeter spoke about overcoming failure, citing the 56 errors he made in his first full season as a pro. He hit on a lot of the usual themes of a graduation speech — dreams, passion, sacrifice — but kept coming back to a central theme: choice, a word he mentioned 16 times in a 16-minute address.

“I challenge you to become champions of hope,” Jeter said, concluding his remarks. “Believe without a doubt that when given one sliver of a chance, your generation not just can, but will reimagine and reconstruct a better tomorrow for all of us. Young people have always responded to their generation’s unique challenges. Following the footsteps of your predecessors, other Michigan alums, step up to the future ahead of you. It is a choice, it’s your choice. Go Blue.”

(Top photo of Tony Gwynn in 1987: Owen C. Shaw / Getty Images)